In the early morning darkness of the moss-draped forests of the Florida Panhandle, teenager Bob Baxter hobbled down a dusty, one-lane gravel road. Blood soaked the back of his jeans and trickled down into his coarse leather shoes. A few hours earlier, he’d been caught running away from the Florida Industrial School for Boys, a reform school in Marianna, a small Jackson County town. His punishment: a beating with a wooden paddle. “I got twenty-five or twenty-six licks,” recalls Baxter.

The year was 1950, corporal punishment was legal in state-run institutions, and this was no ordinary paddle. Roughly two feet long and three inches wide, a network of holes pocked the three-quarter-inch thick board, reducing drag during the disciplinarian’s downward stroke – more bang for the buck, so to speak. The board scraped the rough plaster ceiling with each strike. “You could hear that board coming across the ceiling, click-click-click. Then they hit you right on your butt,” says Baxter. “After about four or five licks, you were numb.”

Halfway to the low brick cottage that served as his temporary home, the boy made a decision: Run. Once again, he escaped into the thick underbrush.

The first time Baxter ran away, he managed to last four days until hunger forced him out of the snake-infested swamps east of the school. But this time, already weak and exhausted, his bloodied buttocks painful and raw, he lasted only two days. School officials found him, took him back to the school, and beat him again. He woke up in the school infirmary. He never ran away again.

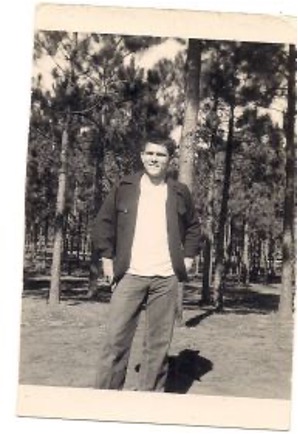

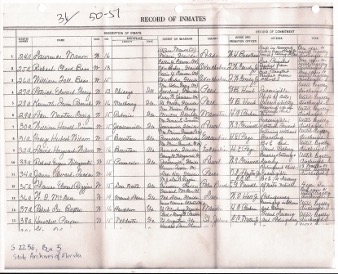

Baxter, now 83, lives in Ocala, Florida, just a few hours’ drive from Marianna. He spent ten months in the school until an aunt arranged his release. The official Record of Inmates from 1950 lists the names of all the boys sent to the school during that period and the reasons for their incarceration. Offenses ranged from the serious (armed robbery) to the mundane (incorrigibility). The entry next to Baxter’s name, in beautiful, looped penmanship, reads, “Growing up in idleness and crime.” Baxter maintains that his alcoholic mother married a man who didn’t want Baxter around, so the two fabricated a story to have the boy – then sixteen – sent to the school. Under the column titled “Term,” it reads, “Until legally discharged.” In other words, indefinitely.

Dubbed “the place where Satan has his seat” by former slaves and Civil War-era Reconstructionists, Jackson County, Florida, had a dark past. A vibrant culture of meanness lurked and thrived in the towns and woods, and the Ku Klux Klan was pervasive. In 1934, Marianna was the scene of one of the most horrific lynchings in the state’s history, when a young black man, Claude Neal, was castrated, murdered, dismembered, and hung up for display in the town square. Marianna seemed an unlikely place for a reform school.

Later named the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, in honor of one of the school’s superintendents, the Florida Industrial School for Boys had a similar dark past. Whistleblowers – past employees, state psychologists, and former inmates – had come and gone for more than a century with no enduring change. But in 2008, a Miami Herald reporter broke the story on the school’s century-long abuses, and a series of follow-up articles in the St. Petersburg Times [now the Tampa Bay Times] revealed even more atrocities – beatings, whippings, forced labor, and rapes – committed in the name of “reform.” The school finally closed in 2011 after investigations by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and the United States Department of Justice confirmed the allegations.

What kind of person does these things to another human being?

Quite often, it’s the sadists among us.

These “everyday sadists” are part of a constellation of malevolent personalities in society. Collectively known as the Dark Tetrad, a term coined by University of British Columbia psychologist Del Paulhus, this nasty quartet includes the narcissist, the Machiavellian, the psychopath, and the everyday sadist. Paulhus explains that these monsters aren’t necessarily in jail or therapy (although they might benefit from the latter), and they survive, even thrive, in everyday society.

Sadists, however, stand out from the group because they live to cause pain. They hurt others, emotionally or physically, just for the self-indulgent pleasure it provides.

The common view of sadism associates the behavior solely with aberrant sexual practices or violent criminal activities. But finding pleasure in cruelty is far more humdrum and frequently manifested among normal, everyday people. In reality, many people exhibit some degree of sadism, albeit on a continuum. These workplace tormenters, school bullies, and Internet trolls lust after cruelty and actively expend time and resources to execute their harm. “Every dark personality’s motivation is usually power, ego, status, or recognition,” says Dan Jones, a psychologist at the University of Texas at El Paso who studies the Dark Tetrad. “But the sadist’s [motivation] is to watch other people be in pain.”

Most dark personalities endure across cultures and age groups and hold some evolutionary leverage even today. But sadism doesn’t bring unique clout to the evolutionary table, according to Jones. “Sadists are engaged in the suffering of others. That is their end goal.”

Eventually, nearly every discussion of sadism comes back to the Gordian knot of nature versus nurture. That is, are sadists born or made?

Behavioral genetic studies suggest that heredity plays a significant role in sadism, according to Paulhus. And brain scans reveal differences in neurobiological structures and activity patterns in the sadist’s brain.

Why have sadists persisted in the gene pool? Paulhus thinks that the sadist’s lack of empathy likely conferred early social advantages whose dividends resulted in reproductive – and therefore evolutionary – success. An openly cruel, vicious person would gain the upper hand in a group, allowing them to rise in social, political, and sexual power.

But the interplay between a person’s natural predispositions and how they choose to cope with challenges and adversity plays a role in sculpting personality, according to clinical psychologist George K. Simon. “The same thing can happen to two different individuals and, depending on how they’re wired, they’ll turn out differently.” Simon adds that the brain is amazingly adaptable, even into adulthood, so it’s difficult to say how much adult behavior, including sadism, is due to nature and how much is nurture.

Whether they’re born or made, sadists often seek out certain types of “enforcer” jobs, such as police officers, school deans, prison guards, and military personnel. That’s a troubling thought for Paulhus. “Sadistic types might gravitate toward [these jobs] because they would have the power to hurt others,” says Paulhus. “They could even be assigned roles where the idea is to hurt people, but they might push it too far.” Paulhus suggests that recent incidents involving police brutality and misconduct underscore the need for appropriate screening for sadistic tendencies in law enforcement job applicants. Most sadists live dual existences, compartmentalizing their mean streaks from their more socially acceptable lives, making identifying them difficult.

University of Texas at El Paso psychologist Dan Jones’ research focuses on finding ways to protect people from the harmful effects of the sadists among us. “Understanding [sadists] is the first step in trying to empower people to prevent exploitation.” Jones hopes to identify ways to deal with these characters so innocent people don’t fall prey to them, but he’s far from formulating conclusive strategies.

Many of the boys who went to the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys turned to lives of violent crime and horrific abuse, punctuated by long periods of jail time and homelessness. Baxter, however, joined the Marine Corps, served in the Korean War, and was honorably discharged. During that time, he married and started a family. But the terrors of Marianna never left his thoughts and eventually reached a tipping point. “When I came back from Korea, I made up my mind – I was going to [the school], and I was going to kill everybody.”

As Baxter packed his things, he looked at his children playing nearby. Not everyone who falls prey to a sadist’s treatment is scarred by the experience; the human psyche has an immense capacity for healing and even growth. Baxter changed his mind. “I never had a childhood to speak of. By God, I wasn’t going to deprive my children of one. They deserved better than that.”

~TLJ

NB: The Florida Senate recently acknowledged and apologized for the acts committed at the school.